Metaphysical decorating is about finding and creating Energy in our environments.. One way to so is through our relationship with objects. This chapter, Energy Through Our Relationship with Objects, explores that quest.

In the first episode of Joseph Campbell and The Power of Myth, Campbell tells Bill Moyers the story of Kirtimukha, a hungry monster. Kirtimukha was created by the god Shiva to finish off a demon who coveted Shiva’s wife.

The would be adulterer shows remorse, however, so Shiva no longer needs Kirtimukha. The monster is starving, however, and he chastises Shiva for creating him. Shiva tells him to just go away and eat himself, and Kirtimukha obliges. As Shiva watches, the monster devours himself until nothing but his head remains. The god was so taken by the event, of life feeding on life, that he rewards the monster by placing his head on the entrance of every shrine to Shiva and many to Buddha.

Campbell explains the lesson of this parable: we have to learn how to live in this world and accept its shadow side of struggle, sorrows, inequity, greed, and cruelty including all the species’ desires to eat each other. Foremost in these challenges for those who are pulled towards spirituality is the need to live with materialism.

Shiva’s homage to Kirtimukha demonstrates that accepting and honoring the material is first necessary before finding the spiritual. He emphasizes this pathway when he tells Kirtimukha,

“He who will not bow to you is unworthy to come to me.”

Finding the Spiritual Through the Material

Honoring the material as a gateway to the spiritual is not something commonly taught. If anything, there is a long tradition of saints, religious leaders, and philosophers whose words and actions might lead us to believe that the material is bad.

Yet, in the West, we love our stuff, and we admire those who have more than we do. Consequently, our anti-materialist teachings, coupled with our lust for things, makes us ambivalent about our belongings.

Why do we see materialism and spirituality as either/or? Why do we think that loving the material is loving the spiritual less? One reason is that:

Western Philosophy has given us the illusion that spirit does not exist in matter.

When we decorate, that is, moving, discarding, or buying new things, we have to address materialism. In metaphysical decorating, however, our relationship with the material and spiritual is unified. We have a relationship with our objects because, like us, we see them infused with a vital life force. There is more inner work in connecting spirit and matter, but it is a more fulfilling way to live. There is no guilt or ambivalence, and we don’t have to choose one over the other. You might give up your objects, but it will only be after they have taught you the life lessons that have to be learned.

If the object is correct for us at present, it will give us energy. If it is no longer of use to us, it will deplete us. Our emotions generally explain how we relate to our objects, which is why Marie Kondo tells us that if an object does not give us joy, we should part with it. [1]

Objects Are Connected to Us

I do not completely agree with Ms. Kondo that if we do not feel joy, we should immediately discard an object. Not having joy means having “something else.” We should look at those “somethings” first, process them, and then say good-bye. Sometimes we feel nothing or mild irritation. Sometimes we feel subtle tugs of unprocessed grief, guilt, or scarcity fears. As we part with the objects that have bonded with us in an unhealthy way, we can also dispel the feelings that keep our energy down. Both an outer and inner cleansing can be accomplished at once.

We are then left with that which connects us to love, joy, and gratitude, freeing us to benefit from our interactions. As we give positive feelings to our things, we feel energized when they send these feelings back to us, in turn..

Objects and the Concept of Body Schema

When I look at the effects of decorating through the lens of metaphysics, it is not science but speculation, a speculation that I consider reasonable. There is a scientific aspect to our relationship with objects, however, which I would like to briefly touch upon. It is the concept of body schema.

Body schema was once thought of as body image, but today they are seen as two different concepts. We can understand body image by examining an anorexic’s misconceptions. In the mirror (s)he, they see an overweight body, when in reality it is dangerously underweight, and the misconception continues to fuel the disorder.

Body schema, on the other hand, is a spatial phenomenon. A well-known body schema disorder is the phantom limb experiences of an amputee. Even though a limb is missing, an amputee might experience its presence with all the sensory experiences of a body limb including pains, responses to the environment, and even maddening sensations like itching.

Body schema involves aspects of both central (brain processes) and peripheral (sensory, proprioceptive) systems. Thus, a body schema can be a collection of processes that registers the posture of our body parts in space. [2] A body schema is constantly updating during movement. It helps us in our balance, re-righting ourselves from the trip on the rug or telling us to duck when we walk under a tree with low overhanging branches. It is a concept used in several disciplines including psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, sports medicine, and robotics.

Body Schema Experiments

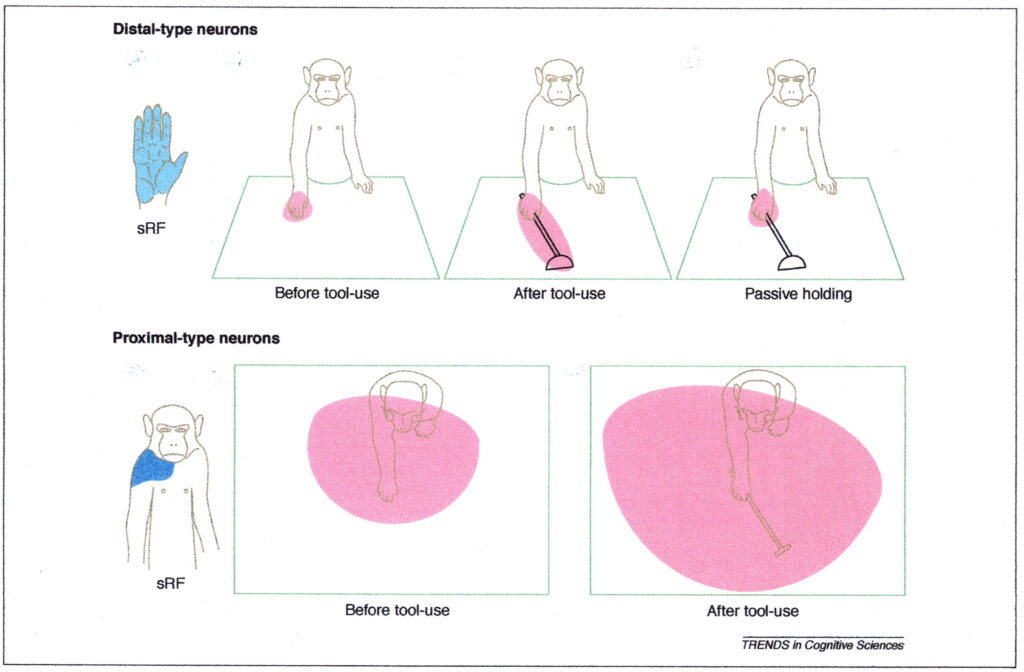

With relation to decorating and our relationships to objects, studies in body schema become interesting. When we use a tool, our body schema changes to incorporate the tool and area of movement. (Note the diagram on Rhesus Macaques showing body schema changing during and after active tool use.) [3]

Our Body Schema and Our Objects

Looking through the lens of the body schema, the objects in use become us, which is one of the reasons people get so upset when certain possessions are negatively affected. For me, losing a contact lens was like losing a part of myself. The same holds true today when I misplace my reading glasses. For many people a minor scrape or dent found on their car is enough to make them believe that a part of themselves has been damaged.

For that matter, driving a car is one of the biggest instances of a tool becoming part of our body schema. When we drive and observe other drivers, their emotions are on display by how their cars move in the subtlest ways. We know when a car is about to cut us off. Though we do not know the specifics, we can feel the driver’s frustration. Cars as tools are a common extension of each driver’s body schema.

Body Schema, Movement and Energy

Questions I started to ask were, “What is considered a tool” and “Couldn’t most anything in our environment be considered one?” ) The definition of a tool is something that helps us do a job or change something. Are the usual examples of the tools held in the monkey’s hand the only examples of tools?

Are they the only things that can change the body schema? I actively move my down quilt to warm myself as I turn in bed at night. Would a functional MRI signify that the quilt has become part of me? What happens when I use my treadmill? Does it also become part of my body schema? And how about my espresso machine? No need to answer that because I know that Nespresso and I share the same soul!

Let’s also think about the things we do not touch with our hands but with the movement of

Our Eyes.

Can it be that when we gaze at an object of beauty, it becomes part of our body schema? What happens when we sit in a room that creates energizing eye movements, beauty, and pleasure? Does our body schema become part of our environment, making a case that everything that surrounds us must be beautiful?

I believe it does.

And with a bow to Kirtimukha, we have to understand that the objects we touch and the objects we see share their energy with us.

Picture Sources:

1 Logo of Mandarin Mansion. Line drawing based on the iron guard of a 15th century Chinese sword in the Royal Armories in Leeds

2 Kirtimukha Asparah Gallery, asparahgallery.com

3 Tumblr via Flickr: Sharon and Peter Komidar

4 deccanviews.wordpress.com

5 tumblr.com

6 en.wikipedia.org

7 know-your-heritage blogspost.com

8. Astamangal, art from Tibet, Nepal and India, info@astamangala.com

***

There are two parts to this website, The Lessons which are more difficult in concept and the blogs which are lighter in nature. Blogs that you might enjoy which have the same theme as Lesson XI are:

A Lesson connected to Lesson XI is Our Relationship to Our Objects and the World, Lesson XII. Besides our individual interrelationships with objects, I believe that what we possess connects us to the subtle energy of other people, other cultures, and the planet itself. Material objects can be the most spiritual of commodities because they lead us to deal with the earthly lessons we are here to learn

Please note that my website allows you to leave comments at the end of the blogs but not at the end of each lesson. If you have a comment or question about a lesson, you may email me at ruta@rutas-rules.com