I love to give paintings as gifts for birthdays and special occasions, especially impressionist floral paintings for wedding gifts. The mathematics of nature make up a major part of their design.

I have an unfortunate attachment to these paintings, though, particularly the good ones. Still, the looming wedding or birthday dates force me to give up these creations. I do tend to work longer on a favored painting based on a fluid promise with no connection to a celebration, for it is hard to see them go.

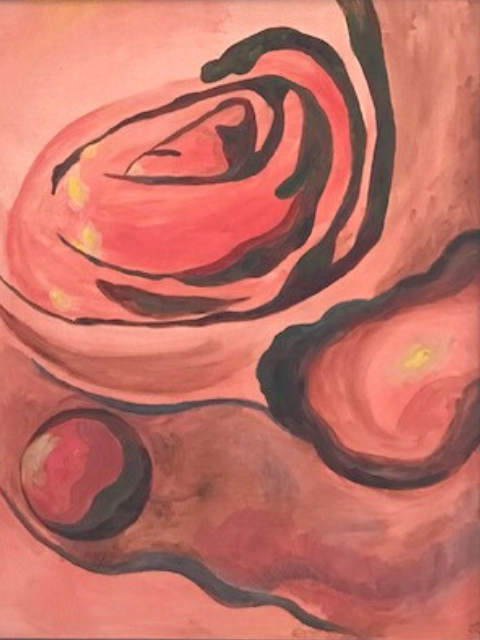

Once, when I promised a favorite doctor a medical painting, I fell in love with it as did visitors to my apartment. That was, until I revealed the true nature of the subject—the inside of a colon.

For years, I had made several attempts to do the painting. The first attempt was similar to my familiar floral impressionist style. Then I decided to imitate Georgia O’Keefe’s style. After all, her floral paintings depicted body parts; why couldn’t I paint the same? No, I couldn’t; I really could not. My attempts were mud. Such an attempt, however, really made me appreciate O’Keefe’s incredible ability. So I found another way.

I think this was my favorite painting and held on to it for too long. Eventually, however, I had to let it go.

The Mathematics of Nature

I sent on the painting accompanied with an essay that reflected my idea that all good design is based on the mathematics of nature. The essay:

The Colon and the Rose

“Everything in the material world has a mathematical blueprint. When we see an object, we also experience its scaffolding on some subliminal level. If this geometry corresponds to the mathematics of nature, the object engenders the energy of beauty.

The ancients believed this mathematical scaffolding existed before matter was created, thus they considered such geometry sacred. Artists up to the Renaissance used these mathematical laws to create architecture and art, thinking these creations needed to follow the limits of the patterns found in nature. Though an infinite set of variations is possible, any deviation could only lead to the visual noise of ugliness.”

*****

As we entered the modern age, artists stopped using absolute rules to define beauty. Only their fancy became the rule, so “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” became the modern definition. Both Plato and Socrates would have raged at that 18th century maxim, for they had fought the Sophists whose definition of truth and beauty was personal whim. Today, some call such relativistic thinking alternative facts.

*****

When I painted that colon for my doctor, I was surprised how much the folds of the colon resembled a rose. The flower’s scaffolding follows the golden mean, a mathematical proportion, which defined beauty in classical times. The golden mean is found in our bodies and throughout the natural world. It dictates the proportion of our bones, the structure of our faces, and the curl of our eyelashes. Even the ratio of our DNA’s length to width has similar mathematical underpinnings as the arrangement of the petals on a rose for each full cycle of its double helix spiral.

Those who have studied the golden mean in nature understand another aspect of this proportion as not just an arbiter of beauty but the most utilitarian way for nature to “pack” its parts into a whole. For instance, we see that the spirals in a sunflower are arranged according to consecutive numbers of the Fibonacci series, creating the golden angle. If these numbers were different or if the angle was off by a degree or more, the seeds would be too thickly packed, stunting growth, or they would be spaced farther apart, leaving the sunflower fewer seeds to procreate.

The petals of the rose are packed in a similar geometric manner to attract bees with their scent. If packed too densely, the petals would be crushed; if packed too loosely, there would be fewer petals and fewer visiting bees.

It would take more than my lifetime to figure out the mystery of the colon’s geometric utility. All I know is that like so many things on planet Earth, some Master’s Architect shaped the colon; and if we see through the lens of those mathematics, then the rose, the colon, and all living things are equally beautiful.

*****

The next time we wait to see our doctors to get our bums and bottoms examined or to undergo that dreaded colonoscopy, we can engage in awe that some master mathematical plan made us perfect and all one. So, “a rose by any other name [truly] smells the same.”

Dedicated in gratitude to Dr. Leon Kavaler and Dr. Jill Kavaler.

***

Leave a Reply