Swarming around each of us are elements that disturb our natural harmony. They are right in front of us, yet I have wondered all my life why we can be so blind to them. To begin to see and experience the harmonious, life-enhancing environments we live in, we need that answer. This lesson, Why People Can’t See, Lesson VI, Part A, reflects that quest.

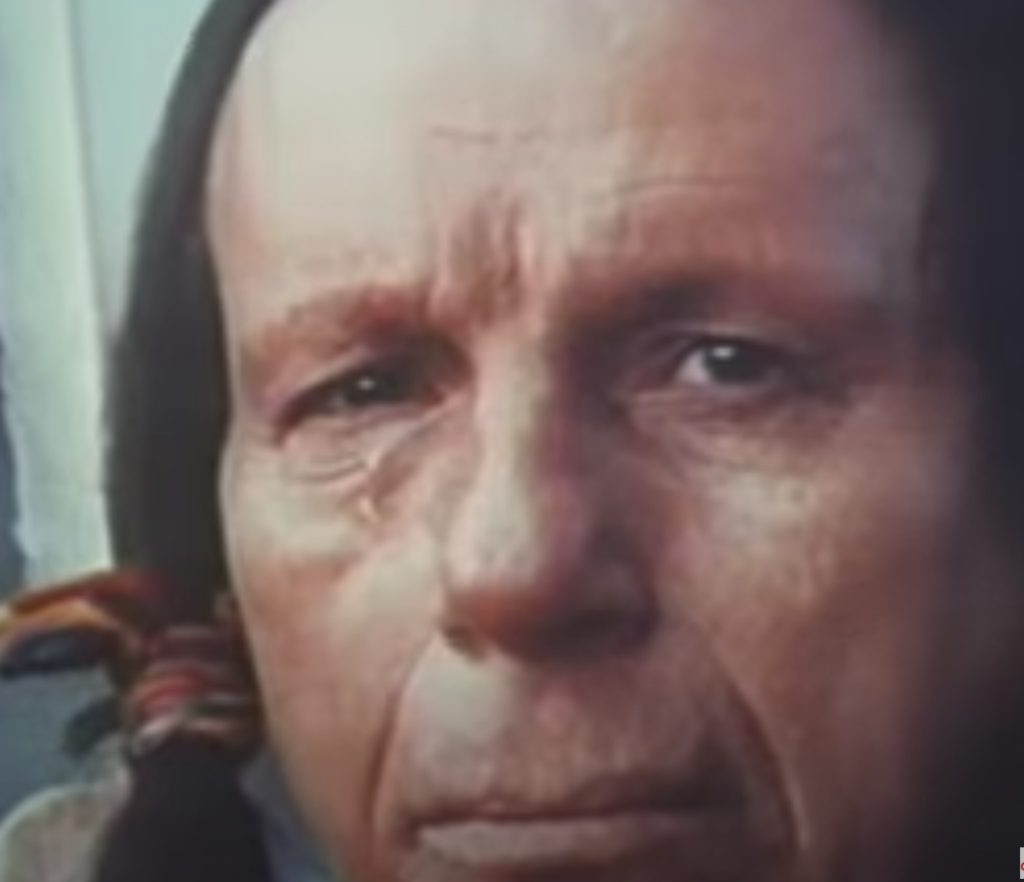

The Most Famous Tear in American History

A visual that still grieves me about our blindness is from a 1971 Keep America Beautiful commercial known now as the “Crying Indian PSA.” A fringed, buckskinned, befeathered figure paddles a canoe in an increasingly polluted river. As he nears a bustling highway along the polluted shore, a paper bag soars from a car window. It splits open at his feet, spilling fast-food debris on and around his moccasins.

The camera pans to Cody’s etched, leathery face. Crawling down his cheek, we watch a tear. It may be the most famous tear in American history.

The camera pans to Cody’s etched, leathery face. Crawling down his cheek, we watch a tear. It may be the most famous tear in American history.

The Story Behind America’s Most Famous Commercial

The tear shows me how clutter, ugliness, litter, and, in general poor design affect us. As if we viewers back then recognized Native Americans’ reverence for the land and their ecological wisdom, here was as an actor posing as one. Yet, when the public service announcement aired, we widely ignored Native American wisdom, if we appreciated any of it at all, as the historian Finis Dunaway put it in Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images.

Moreover, Iron Eyes Cody, the ad’s actor, was of Sicilian descent. Despite credits including more than 200 films as an Indian, he harbored anti-Native American sentiments

How the Environmental Movement Was Fooled

According to Finis, the shedding tear’s most significant duplicity was that the public service announcement sponsor, Keep America Beautiful, staunchly opposed important environmental initiatives. American Can Co., the Owens-Illinois Glass Co., and other leading beverage and packaging corporations founded it in 1953. Coca-Cola, the Dixie Cup Co., and others joined later. The commercial’s purpose was not to save the environment. It was to shift the litter’s blame from the corporations to individual Americans.

In a deep anguished voice as the famous tear appears, the narrator intones: “People start pollution. People can stop it.” The ad made “individual viewers feel guilty and responsible for the polluted environment,” Finis writes. It placed responsibility “entirely in t

he realm of individual action, concealing the role of industry in polluting the landscape.”

Beverage producers themselves, the very founders of Keep America Beautiful, were a major cause of the worsening litter. They were also responsible for vast mining of natural resources; for various additional kinds of pollution, and for “the generation of tremendous amounts of solid waste,” Finish wrote. Yet, “the Keep America Beautiful leadership lined up against the bottle bills.”

As the Keep America Beautiful began fighting legislation to require beverage producers to sell their products in reusable containers, the National Audubon Society, the Sierra Club, and other mainstream environmental groups resigned from its advisory council.

The most famous tear shed in America is still real for many of us echoing the unanswered question why people don’t see.

How the Brain Helps Us Not to “See”

Twelve years ago, I completed a small renovation on our apartment. It was painted and the floors were buffed. I bought a new couch and curtains. I pretty much finished all of it, except for some bathroom items and a light fixture in the hall. We finished the bathroom quickly enough, but the hall light fixture I wanted was on back order. Eventually, it needed to be reordered. After a while, I just forgot about it. Day after day I walked under the lone light bulb dangling from a wire from the hall ceiling until I couldn’t see it anymore.

I am sure you can find your own example of the hanging light bulb. We all do it. It is not as if we don’t see it. I saw the light bulb every day with my eye/brain. Somehow, however, the mind blocked the brain’s input. This is a common neural adaption.

The Overworked Brain

The brain is like a computer on steroids. It processes ten million pieces of information per second. To deal with this overload, it chooses efficient ways to organize information. According to neuroscientists, one way the brain deals with consistent input is to ignore it. The brain thinks, “Same ol’, same ol’.” To preserve energy, it simply stops noticing. This continues unless one specifically directs one’s attention to it. I refer to this perceptual adaptation as a “cognitive override.”

So, poor design, street garbage, and a hanging light bulb is simply not “seen.” Consequently, it can’t be changed.

The Effects of Not Seeing

Unfortunately, it is not just the body or mind that is affected by what we see. Another part of the human persona is affected. It is not known through science but only known in the laboratory of one’s own personal experience. Let’s call it “the subliminal self.” It pulls in the beauty that makes us feel alive.

Sadly, one’s subliminal self is not subject to a cognitive override. It searches for patterns constantly, seeing everything. So when it comes to bad design or litter, a perfect storm sets in. Our brain, through a cognitive override, dismisses these negative erratic patterns. But the ever-vigilant subliminal self sees them all and experiences fatigue from all the visual noise. We see the disharmony, and “feel” their effects but override the fact that we do.

Not “seeing” creates a lot of other problems. Studies have shown that the continuous existence of litter, despite not being noticed, inspires more litter.

To get people to stop littering, there must be no litter. It’s a Catch 22.

Even though we only need to see a few details to perceive an object, paradoxically we see everything. This means we see the scratches on the baseboard, the heel scuffs on the floor and the gum on the sidewalk. We see the grime on the light switch, the broken cabinet handle and the smudges on the stainless-steel refrigerator…

In real life, you can’t get rid of all the items that create visual noise, but we can eliminate most of them.

The first step is overriding the cognitive override.

To use decorating to enhance our lives, we must become aware when we are not “seeing” what we see.

The Ego and Vision

On one occasion, I helped a colleague in the public schools decorate her new office. She shared it with two others. The custodians painted the room battleship gray. A few holes were left in the ceiling from vent openings. There was a general din of dirt, rusted linoleum and unfinished woodwork. There was little money in the schools for aesthetics, so she undertook changing her environment on her own. She asked me if sponge- painting the wall would help. Yes, I said — after we deal with all the clutter. She said that she would paint, but only her section of the room, which a storage cabinet bordered on one side and a shelf the other.

I tried to explain to her that decorating is done to get Energy. Everything we see effects us and if the other parts of the room were left gray and dull, she would still see them and be depleted. The only solution would be to decorate the whole room. She did not want to spend the effort decorating the whole room and nothing I said could make her change her mind. With a sigh, I thought of the Talmud saying: “We don’t see things as they are; we see things as we are.”

I realized that her concept of perception had to do with territory and was an ego form of thinking. She couldn’t see the whole picture, only her part even though her subliminal self saw everything and was depleted. To get energy in our environment, we must look at it as a series of patterns encompassing the whole not as individual ego parts.

Seeing “Nothing” Because We Are Told to Do So

I was told as a child that cellophane tape was great to use in art projects because it was invisible. I could, however, always see it. Even Scotch Magic Tape, the kind that is frosty and supposedly invisible on paper, calls my attention.

It was always one of my pet peeves to see posters hung with several inches of cellophane tape extending two to three inches onto the wall. The school lacked the money to frame the posters, but I felt that they could still be displayed aesthetically.

Decorating with the Mad Tapers

I often worked with a group of students to do school beautification work. We’d came to a classroom’s “great poster” wall holding a history of long-gone posters, papers, and flyers. All that remained would be bits of cellophane tape, hundreds. Head and age would fuse some of it to the wall. Some would have black edges, magnets for trapped dust. Not to worry, I was told, since nobody saw this “invisible tape.” The students were not seeing the tape, but were seeing the symbol of what the tape meant to them through conditioning and education.

xxx

Mad tapers are everywhere. Wherever we go, we find signs of communication in , bathrooms, doctor’s office, classrooms and hospitals, post offices, and all public buildings. We may even do it in our own homes. Using a tape roll on the four back corners is of the same cost. Matting or framing in an inexpensive frame calms down all the details, leading to more visual harmony. Offices of financial means do this.

Seeing Affected by Community Pressure

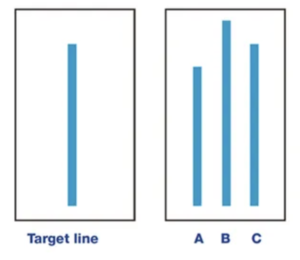

One of the most interesting studies about perception took place in 1951 by Solomon Asch, a Gestalt psychologist. It was more than a study on visual perception, it was how an individual’s visual perception was affected by the opinions of the community. Asch gave the participants a card with three different length lines. He asked the participants to tell which were longer or shorter.

Unknown to the participants were people acting as participants, called confederates. They were placed to determine how their responses would affect the real participants. At first the confederates, who were always called first, gave the correct answers. Eventually, the confederates purposely gave the wrong answers.

Initially the true participants went along with the correct answers but when three confederates gave the wrong answers, many of the true participants started giving incorrect answers.

The Results

Asch was shocked to find that about one third of the participants went along with the erroneous majority on all the vision tests. In some tests, 37 out of 50 went along with the erroneous material at least once.

When asked later about their performance most of the true participants indicated that they knew they were giving wrong information. They wanted to go along with the group for fear of ridicule for their lack of conformity. A few participants said they actually believed the incorrect information was correct. They actually “saw” what the confederates said they saw. Their brains cognitively overrode their true perceptions.

The experiment had far reaching ramifications. The country had just come out of WWII which saw the effects of the holocaust. Questions arose about how societies could have allowed this to happen. The Solomon Asch studies proved how easy it was to affect a person’s judgment. If a simple visual perceptual experiment could be affected by group pressure, how easy would it be to have group pressure affect the individual’s moral compass.

If those around us don’t “see,” does this affect our ability to see our environment? Will our need to conform also blind us?

As We Search for Answers Why People Don’t See

I think that there may be a lot of factors that cause people not to “see.” advertising manipulation and social conformity issues are one. The ego and territorial issue are another. The brain’s desire to ignore stimuli to ovrrrcome stimuli overload is another.

The questions just bring up more questions. And I have one more big one. It is a stretch but worth the perusal. In Why People Can’t “See,” Lesson VI, Part B, we will continue the quest.

***

There are two parts to this website, The Lessons, which are more difficult in concept, and the blogs, which are lighter in nature. Blogs that you might enjoy with the same theme as Small Spaces are:

Two Lessons that relate to this blog are:

Please note that my website allows you to leave comments at the end of the blogs but not at the end of each lesson. If you have a comment or question about a lesson, you may email me at ruta@rutas-rules.com